![]()

|

Himnusz National Anthem Send E-mail Visitor Number since 06/25/99 Created 12/30/96 |

Life

before the Revolution

Life

before the Revolution

I lived in a 3 story apartment building located just two blocks from one of the major railroad stations, the keleti pájaudvar, or East Station.

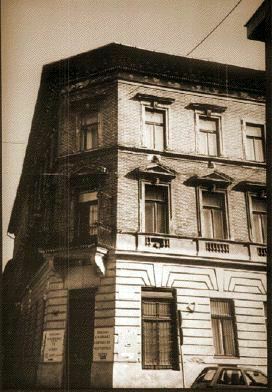

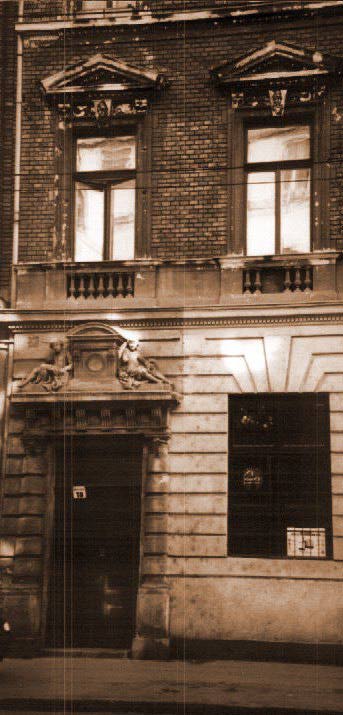

It is at number 18, Nefelejts utca (Forget-me-not Street) at the corner of Péterfy Sándor utca. The location was ideal; every major attraction in the city was within walking distance; downtown, less than 2 km, City Park less than 1 km; major shopping and restaurants on Thököly and Rákoczy út, just a couple of blocks away. The neighborhood, which was part of the 7th district, was apparently dubbed "Chicago" by the old-timers because it grew so rapidly prior to the turn of the century (1900). As you can see from the pictures, it is an old, ornate building, probably built in the mid 19th century, of brick and stone. It seems that no cost was spared back then; just look at the intricately sculpted door and window details. That it survived through two world wars and countless revolutions is a testament to the skill of the architects and craftsmen of the day. |

|

This building still stands today. It has aged considerably since we left in 1956 and is now considered a historic site. By all means, try to stop by if you are ever in Budapest. |

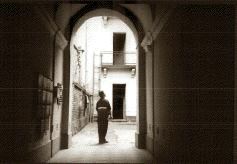

Upon entering the front door from the street (below left), there is an arched tunnel (below) leading to a central courtyard.  The courtyard is ringed on three sides with outdoor galleries which provide access to the kitchens of all the apartments (below). We lived on the top floor, at number 12. There were also formal inner stairways which led to the main hall entrances of the apartments.  |

Our apartment is on the top floor of this building, with the outer windows facing Péterfi Sándor street. To the best of my recollection, the main entry is from a formal stairway into a hall with two large rooms at one end and the kitchen at the other. The first large room was a parlor while the second, which opened from the first was the bedroom. There was a large brick coal burning fireplace in the bedroom. In winter, we kept the bedroom door open to heat the whole apartment. My mother, grandparents and I all slept in the bedroom. The kitchen had a gas stove with oven and a large pantry and sewing room. I remember my grandmother working on her old Singer foot operated sewing machine. We had no refrigerator or hot water. The huge bathtub in the bathroom was rarely used; we bathed in a smaller tub filled with water heated in the kitchen.

My grandparents had some very valuable furnishings, all in the parlor where I was rarely allowed to play. In the upper right corner (see diagram below) was a grand piano which my grandmother played quite proficiently. In the upper left was a magnificent desk and chair that was fit for a head of state. Along the right wall was a floor to ceiling bookcase filled with books in German, French and English, in addition to Hungarian, all of which my grandfather could read with ease.

As far as apartments went in post-war Budapest, this was a very good one.

I went to school a few blocks away. I was just starting third grade when the revolution broke out in the fall of 1956. My grandmother took me to school and picked me up, every day. Of course, we walked. I was never allowed to play in the street, it was considered "low class". The school was quite strict in enforcing discipline; when a kid got in trouble at school he would naturally be punished then and there, but then his parents would punish him again at home for the same misdeed. Parents didn't sue teachers in those days.

In the lower grades (up to third or fourth) we wore blue kerchiefs with our uniforms and were called pajtás "little comrades". In the upper grades, they wore red kerchiefs and were called úttörö "pioneers". These were, of course, terms used by the Communist Party in the lifelong indoctrination process (which, fortunately, was a dismal failure, as was Soviet-style communism itself). The teachers called us by our family names only and we called them tanitónéni "Mrs. Teacher" (loosely translated). The teachers all wore white lab coats and were terribly mean! However, the quality of teaching was second to none, as you have surely discovered that ex-Hungarians have done extremely well in the world. (I just learned recently that the CEO of Intel, Andrew Grove, is a Hungarian who also escaped in 1956. He was selected Man of the Year by Time magazine.)

My mother worked as a draftsman at a company which designs industrial and commercial and military buildings (Általános Épületi Tervezö Iroda - General Building Design Bureau). She was in plumbing, heating and ventilating. She attended technical school at night. My grandfather was an official at a bank. He brought work home with him every day and typed away at his ancient typewriter until the wee hours. Remember, we all slept in the same room? I am now a very deep sleeper, no doubt owing that trait to my grandfather's typing! My grandmother was the housewife who stayed home and cared for us.

School and work went through to Saturday noon. On Saturday afternoons and Sundays, either my mother or grandfather would take me places. My mother always hung around with her friends and I received a lot of attention from them, especially from the young men who may have wanted to date her. My mother would take me to the City Park, the Danube shore, the Fisherman's Bastion and castle across the river, or up the mountain on a narrow gauge railway. My grandfather would take me to the thermal baths (which were originally built by the Romans) on Margit Sziget (Margaret Island) or ride the old subway from the city center to the end of the line at the amusement park. (This was the first subway on the continent of Europe, outside of England, opened in 1896.)

Communist indoctrination was pervasive throughout society, not just in school. I remember accompanying my grandmother to frequent szeminárium "seminars" extolling the virtues of communism. I didn't understand, nor did I pay attention to that stuff. My grandmother went because she feared that she was watched by the building superintendent, who was typically the AVO's (secret police's) local informant. Fortunately, most Hungarians took this lightly as evidenced by the underground humor mill.

My mother has an amusing example of this indoctrination and how Hungarians took it in stride. When she told us this story at home, she did so in a hushed voice, just in case. At her office, drawings were produced on tracing paper which is similar to toilet paper but somewhat stiffer. In any event, since paper products were expensive and in short supply, toilet paper was not provided in the company rest rooms. The employees, therefore, would not only use tracing paper to take care of their sanitary needs at work, but also took some home. The management took great pains to explain to the employees that stealing tracing paper was tantamount with conspiring with the peoples' enemies and would undermine communism itself. They went as far as to post this poem in the rest rooms:

|

Aki pauszpapírt használ! |

is conspiring with the enemy) |

Whereupon an obedient worker, not wishing to undermine communism, responded with the following graffiti:

|

Törlöm seggem Szabadnéppel. |

I wipe my bottom with the "Free Nation" - communist newspaper) |

|

Epilogue |

Return to Home Page |

|